Reading & The Brain: How Kids Learn to Read & Decodable Books That Help

Posted on January 8, 2025 at 6:00 am

By Tammy Henry

Cracking the Code

Learning to read is learning to break a complex code.

Unlike speech (how we produce words and sounds) and verbal language (how we communicate ideas and information), reading is not hardwired in the human brain.

There is not a “reading” region of our brain. Instead, at least three different parts of the brain—sound discriminations, language comprehension, and recognition of letter shapes—are used to create meaning from the marks made on paper and other surfaces.

In the English language, there are 26 letters and 44 phonemes (fow-neems). Phonemes are the different sounds we make when we speak. This means letters may make more than one sound, such as short and long vowels, and letters can be combined to make a new sound, such as sh and oi. To make reading even more complex, we have letters that don’t say what they are supposed to, like gh in laugh and that tricky silent e in dive and plate.

With good instruction, humans can indeed learn to read.

Methods of Instruction

So, what does this “good instruction” mean and look like? The answer is complex. Schools have tried many methods with varying degrees of success. Some educators are passionate about certain methods, which can include phonics instruction, whole language, and balanced literacy.

Phonics directly and systematically teaches sound/spelling correspondences. Children learn the individual sounds of letters and letter combinations. Phonics instruction has been criticized for teaching letters and sounds as rote memorization with no direct correlation to actual reading.

The Whole Language approach teaches children to memorize words by sight. This is taught in a language rich environment with authentic literature and not “dumbed down” readers. Whole Language emphasizes teachers reading aloud often and pointing out whole words to their students. Their mantra is “you learn to read by reading.” However, when reading on their own, children can only guess what a word might be by the context of the story if it is a word they haven’t memorized.

Balanced Literacy incorporates both phonics and whole language, by teaching some phonics and sight words. However, this approach also encourages children to skip a word they don’t know and come back to it later, look at the picture to work out the word, or try a word that seems to make sense. This method often involves the child guessing some words instead of actually reading them.

Through the years there has been polarization about which reading approach is best for students in curriculum, schools, and among teachers, often referred to as “The Reading Wars.” Phonics, whole language, and balanced literacy all have positive aspects, but individually, each method doesn’t fully teach reading to children.

As children begin to learn to read, they are given books that are known as leveled readers. These books are categorized according to the amount of white space on the page, the font size, the length of the words, the number of words on a page and/or in the book, and the complexity of the plot. Most of these books are based on repetition and picture clues.

For example, in Michael Robertson’s I Like My Car, each colorful two-page spread shows a different animal driving a different color car with the phrase, “I like my (color) car.” Children do not necessarily need to read the words because it is a repeating phrase, and they also don’t have to read the color word because they can see what color the car is from the picture.

Yes, children and adults are excited that the child can “read” the book. But many might wonder: if given the same words in isolation or without picture cues, would the child know the word?

That said, leveled readers do expose children to sight words and common words, build reading confidence, and are one of several tools that can help break the complex code of reading.

The Science of Reading

In recent years, the method called The Science of Reading has emerged which encompasses research-based approaches to reading instruction and considers all aspects of how children learn to read and comprehend text.

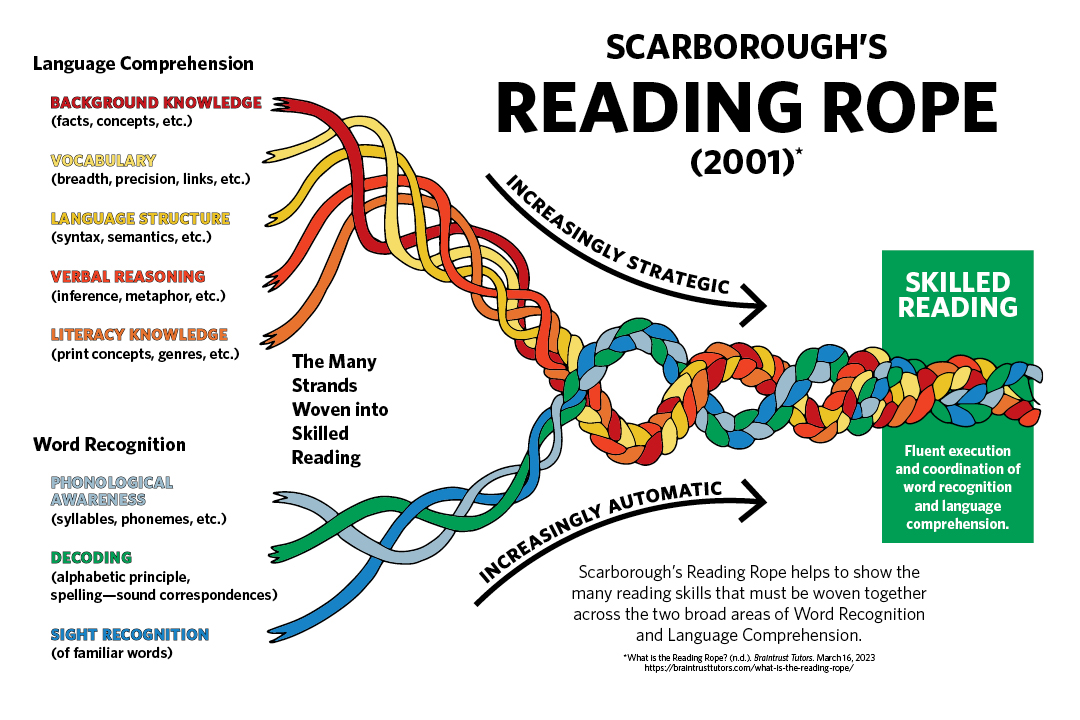

Scarborough’s Reading Rope provides a visual representation of this more comprehensive look at how we learn to read (figure 1).

Reading includes both word recognition and language comprehension. Word recognition includes three important parts:

- Phonological awareness: Hearing the smaller sounds within words

- Decoding: Knowing the letter and letter-sound correspondences

- Sight recognition: Knowing high frequency words, often those that cannot be sounded out, such as the or said

Children are systematically taught letters and letter sounds (basic phonics) and then practice those letter sounds as they sound out words in what are known as decodable readers.

Decodable readers differ from traditional early readers in that the majority of the words in the book contain only letter sounds and sight words that the children have been directly taught at the beginning.

For example, in Kim Thompson’s Not a Rock, children learn the letters and letter sounds for b, d, h, p, r, s, t, and k (spelled ck) and also the short o vowel sound in the introductory pages. Also included are a handful of high frequency words for readers to recognize. As children (and their adults) read this book, they are able to decode (sound out) the words in the context of the story because all the letter sounds have been explicitly taught before the story begins.

When read with an adult, these decodable books provide children with a strong guide for word recognition, a strand of Scarborough’s Reading Rope.

Books to Borrow

You can find decodable books and others for young readers on our shelves and also as eBooks with these digital resources:

You can find decodable books, easy readers, and other children’s books using these curated booklists put together by our youth collection development librarian:

- Decodables & Phonics

- The Best & Newest Easy Readers for Kids

- Other curated lists for kids in our catalog

Learning to read is complex and takes a lot of time, effort, instruction, and practice plus a lot of patience for the adults who are helping.

The phrase “slow is fast” can be applied to children learning to read. In order to become successful readers, children must thoroughly understand and know the basics of letters and letter sounds, which takes time (the slow part). Once they develop their reading skills, they might zoom through books (the fast part) or move on to books that challenge them.

Even though the children in your life are learning to read, it is important to continue to read aloud to them!

We suggest choosing picture books and short chapter books with rich and complex language. This develops one of the other strands of Scarborough’s Reading Rope, language comprehension. Combined with word recognition, both strands are needed to become a confident and successful reader.

Tammy Henry is a librarian, focusing on early learning and youth programming, at Spokane County Library District. When not at work, she is busy volunteering with her church, recording memories on a family blog, and reading loads of books—picture books, biographies, fairy tale retellings, kids’ graphic novels, and regency romances.

Tags: books, children, comprehension, decodables, early learning, kids, parents, phonics, reading, teachers